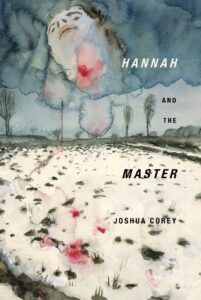

My special guest today is poet Joshua Corey and we’re chatting about his newest collection, Hannah and the Master. (MadHat Press, 2021)

My special guest today is poet Joshua Corey and we’re chatting about his newest collection, Hannah and the Master. (MadHat Press, 2021)

Bio:

Joshua Corey is a poet, critic, translator, and novelist.

He lives in Evanston, Illinois with his family and teaches English at Lake Forest College.

What do you enjoy most about writing poems?

Of all the different kinds of writing, poetry permits me to think with the highest fidelity to what my thought process is actually like. In a poem I can be entirely associative, letting one image or pattern of sounds lead me to the next, trusting to the force field of associations to hold the thing together. That means the poems are the truest and richest record of my inner life—which may also make them opaque to some readers, but that’s okay. I think the people who are drawn to poetry are drawn to that dialectic of intimacy and opacity.

Can you give us a little insight into a few of your poems – perhaps a couple of your favorites?

Back in the 1920s, Martin Heidegger was a rising star in German philosophy, and Hannah Arendt was his adoring student. They had an affair, and after it ended, the relationship continued to play out in both of their lives, even after Heidegger joined the Nazi party and Arendt, as a Jew, was forced to flee Europe for the United States. Later on, of course, Arendt wrote Eichmann in Jerusalem and coined the concept for which she’s most famous, the banality of evil. Hannah and the Master is a fever dream inspired by that story, retelling some of its key points in an almost science-fictional register—in my book, Heidegger and Arendt become Blade Runner-style replicants re-enacting their romance in a new century that promises to be as apocalyptic as the preceding one.

I’m not sure what to call this book, frankly: is it an epic poem, a collection of poems, a novel, a madman’s notebook? Most of the poems toss up pieces of language taken from my principals and let them resettle into new patterns. Two sections of the book, for example, consist of homophonic translations of poems written by Heidegger and Arendt, in an attempt to suss out the strangeness of that relationship. Another section reimagines the story of Rahab from the Book of Joshua, with my Hannah figure playing the role of the woman who kept faith with the Israelites without actually being one of them. Other poems collage language from Simone Weil, Paul Celan, W.H. Auden, and other twentieth-century replicants. I don’t know how lucid it will be to readers, but I hope they’ll be moved by the intensities.

What form are you inspired to write in the most? Why?

I do like traditional forms, particularly the sonnet—my 2011 book Severance Songs consists entirely of postmodern or deconstructed sonnets, and I could see myself taking on the form again for a future project. But collage has probably been the most important formal technique in my poetry. I don’t usually collage in the literal sense—I don’t cut and paste sentences—but my brain is crammed with things I’ve read and heard, from soap advertisements to King Lear to video-game dialogue to Emily Dickinson—and it all comes out in the poems.

What type of project are you working on next?

What type of project are you working on next?

I’ve got an autobiographical novel coming out this fall from Spuyten Duyvil Publishing, and I’m finishing a trilogy of science-fiction novels about the consequences of trying to ride out climate change by building literal and virtual arks.

When did you first consider yourself a writer / poet?

My mother wrote plays and poetry and she was a devoted reader of poems (and mystery novels, and other things), and she impressed upon me from an early age that a writer was the noblest thing to try to be. So I was hooked from a very early age—I never had a chance to be anything else, really.

How do you research markets for your work, perhaps as some advice for not-yet-published poets?

I don’t know a better method than reading widely, and seeing where the poets I most love are being published (the acknowledgments pages of your favorite poet’s most recent collection is aa good place to start), and then sending some of my work to the same websites and journals.

What would you say is your interesting writing quirk?

Before the pandemic it was probably my love of writing on the commuter train I take from Evanston to Lake Forest and back again every day; the 35-minute ride provided for me the perfect amount of writing time because it was enough time to make progress on a project but not so long I’d get the fidgets. Hopefully I’ll get back to that this fall; all work and no train makes Josh a dull boy.

As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up?

I’m a child of the 70s and the space program and the original Battlestar Galactica, so: an astronaut, duh.

Anything additional you want to share with the readers?

As a reader I find nothing more inspiring than an author’s freedom on the page—the sense of liberation from constraints I find in Virginia Woolf or John Ashbery or Rachel Cusk—the sense that, in the book I’m reading, the voice of the speaker might do anything, say anything. I hope that readers will find some of that freedom in my work.

Thanks for joining me today, Joshua.