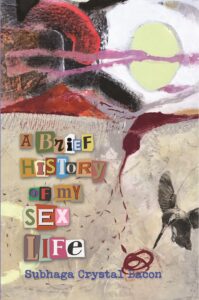

Poet Subhaga Crystal Bacon is chatting with me about their new collection, A Brief History of My Sex Life.

Bio:

Subhaga Crystal Bacon (they/them), is the author of five collections of poetry including, A Brief History of My Sex Life, Lily Poetry Review Books 2026; the Lambda Literary finalist, Transitory, 2023, winner of the BOA Editions, Ltd. Isabella Gardner Award for Poetry; and Surrender of Water in Hidden Places, winner of the Red Flag Poetry Chapbook Prize, 2023, released in an expanded second edition in the summer of 2024. A Pushcart and Best of the Net nominee, Subhaga has been an AWP Writer to Writer mentor and is a teaching artist working in schools and libraries with youth and adults, as well as private students. Their work appears or is forthcoming in a variety of print and online journals including Terrain, The Diode Poetry Journal, The Bellevue Literary Review, Indianapolis Review, Smartish Pace, and others. A Queer elder, they live in rural northcentral Washington on unceded Methow land.

What do you enjoy most about writing poems?

Writing poems is a way for me to understand myself better, to process ideas or feelings that are often lurking below conscious thought. I’ve described this as the feeling that precedes a sneeze. I get a bodily sensation that there’s something that wants to come forward. Capturing this feeling, or idea that’s been following me helps me to unpack it and see what it has to offer. I enjoy seeing where the application of poetry to this emergence will take me. Even if the resulting poem isn’t very “successful,” the writing brings me greater clarity than I had before I began.

Can you give us a little insight into a few of your poems – perhaps a couple of your favorites?

This collection is such a departure from my previous book, Transitory, which was a catalog of trans and gender nonconforming people murdered in 2020. My dear, late, friend, the poet Jennifer Martelli, who was my best first reader, asked me while I was drafting that book: where are you in here? That question both rounded out Transitory and gave rise to the new book. Many of these poems were hard to write. My current favorites are those that are in the later part of the final section where I’ve arrived at a deeper and more welcoming self-knowing, such as “Self-Portrait at the End of a Season,” “Pro-Nominal,” and “If I give you my heart will you promise not to break it,” which comes from a Lucinda Williams song.

What form are you inspired to write in the most? Why?

I’m obsessed with the sonnet. I’ve had to wean myself from getting close to fourteen lines and thinking “sonnet!” Still, I love the sonnet’s restriction and flexibility. It’s a poem that was designed to create a kind of constraint, the little room, the cell. And that lends it a kind of flexibility. What’s in the room? Why am I in the cell? What’s beyond it? And certainly, in the last few decades, we’ve seen its flexibility: Wanda Coleman’s “Heart First into this Ruin,” Terrance Hayes’ “American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin,” and Diane Seuss’ “frank, sonnets,” which was a great inspiration to me. Even beyond the form of the sonnet–its fourteen lines and potential rhyme–its structure is compelling and often organic. If the poem begins one place then arrives at a kind of turn to something else, some clarification, then it’s a sonnet in its bones. It’s just such a useful, and I think user friendly form.

What type of project are you working on next?

My next project is a more outward looking collection tentatively titled “humaNature,” an examination of humans and nature in cultural and climate crisis. I’ve been writing poems about changes to the natural world as witnessed in Washington State, which has a wide variety of ecosystems. I did two residencies at Mineral Arts and Residencies in the small town of Mineral in rural southwestern WA. It’s a different climate than the high desert shrub-steppe where I live. The manuscript also has a number of poems about the impact the current administration is having on the natural world and human lives as part of that ecosystem. The poem that recently appeared in Terrain, “Anti-Trans Legislation at What Feels Like the End of the World”–a sort of insanely long title for such a short poem–really gets at the way you can’t separate treatment of humans from treatment of the earth itself.

When did you first consider yourself a writer / poet?

From a very early age, I thought that I would be a writer. By the time I was an undergraduate, poetry was everywhere. All of my friends seemed to be “doing it.” I remember thinking, “I should write poetry, too.” My very first reading was on my college campus; it was an exchange program with students from a nearby state university. One of my English professors, who was our poetry mentor at the time, introduced me as a “closet poet,” which got a big laugh from the largely queer group of visiting poets. I started to write and submit poems to the college literary magazine, and that was it for me. I kept writing from then, my early twenties, until now.

How do you research markets for your work, perhaps as some advice for not-yet-published poets?

For me, the best way to research markets is to read. I subscribe to a large number of literary magazines, Poetry, for example, I read religiously along with Agni, Poetry Northwest, and others. And reading other poets’ collections. I always read their acknowledgements pages and then check out journals that are new to me. Then I go online and read what else those journals have published. It’s hard enough to find homes for our work without sending poems that are not a good fit for the journals receiving them. I also subscribe to Duotrope, and Chill Subs. These are easy to skim for upcoming deadlines. My first post-college publications all came from the classifieds section of Poets & Writers. There are folks who’ve paved the way for us, and we should follow their paths.

What would you say is your interesting writing quirk?

I start formatting the shape of the poem from the get go. I tend to revise as I write then go back and revisit what’s there. For me, the shape of a poem–one stanza or more? Regular line lengths or varied? Organic or formal stanza length?–is an obsession. I admire poets who trust long single stanza poems, but I’m not there yet. It may be part of how my divergent mind works. Too much to take in all at once, so I fool around with what feels digestible in terms of the poem’s shape: couplets, tercets, quatrains, or organic “paragraph-like” stanzas.

As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up?

I wanted to be a writer, which is odd since I came from a very non-literary family. My mother was an avid reader of popular novels of all stripes, but we didn’t have books in our home beyond the encyclopedia or the schoolbooks we brought home. Somehow, I think because I was an early reader who fell in love with books in school, I had a pull to write, though, as I said above, it seemed that I stepped into it because it was what everyone else was doing. I was lucky to work in higher ed for many decades, which supported my writing until I could retire and give it my full attention.

Anything additional you want to share with the readers?

I believe that poetry is for everyone. It’s not something only for “intellectuals.” As William Carlos Williams said, “It is difficult to get the news from poems yet men die miserably every day from lack of what is found there.” I believe there’s something for everyone in poetry, and the more exposure people get to it, the more they will benefit. I used to tell my students to keep a volume of poetry next to their beds and read a poem a night. Not to worry if it “made sense,” just to let it wash through them. I believe it enriches our hearts and minds. I subscribe to so many “poems a day” that I spend the day parsing them to see what resonates. Especially now, when the news is so literally horrible, poetry is essential because it distills experience and often speaks truths that we may not even have known we needed until we read them. It brings us voices and views that may be very different from our own and without which our lives are poorer.