Novelist Elizabeth Gauffreau chats with me about her new 20th century historical fiction, The Weight of Snow and Regret.

Bio:

Elizabeth Gauffreau writes fiction and poetry with a strong connection to family and place. Her work has been widely published in literary magazines, as well as several themed anthologies. Her short story “Henrietta’s Saving Grace” was awarded the 2022 Ben Nyberg prize for fiction by Choeofpleirn Press.

She has published a novel, Telling Sonny, and two collections of photopoetry, Grief Songs: Poems of Love & Remembrance, and Simple Pleasures: Haiku from the Place Just Right. Her latest release is The Weight of Snow and Regret, a novel based on the closing of the last poor farm in Vermont in 1968.

Liz’s professional background is in nontraditional higher education, including academic advising, classroom and online teaching, curriculum development, and program administration. She received the Granite State College Distinguished Faculty Award for Excellence in Teaching in 2018. Liz lives in Nottingham, New Hampshire with her husband.

Welcome, Liz. Please tell us about your current release.

For over 100 years, no one wanted to be sent to the Sheldon Poor Farm. By 1968, no one wanted to leave.

Amid the social turmoil of 1968, the last poor farm in Vermont is slated for closure. By the end of the year, the twelve destitute residents remaining will be dispatched to whatever institutions will take them, their personal stories lost forever.

Hazel Morgan and her husband Paul have been matron and manager at the Sheldon Poor Farm for the past 20 years. Unlike her husband, Hazel refuses to believe the impending closure will happen. She believes that if she just cares deeply enough and works hard enough, the Sheldon Poor Farm will continue to be a safe haven for those in need, herself and Paul included.

On a frigid January afternoon, the overseer of the poor and the town constable from a nearby town deliver a stranger to the poor farm for an emergency stay. She refuses to tell them her name, where she came from, or what her story is. It soon becomes apparent to Hazel that whatever the woman’s story is, she is deeply ashamed of it.

Hazel fights to keep the stranger with them until she is strong enough to face, then resume, her life–while Hazel must face the tragedies of her own past that still haunt her.

Told with compassion and humor, The Weight of Snow & Regret tells the poignant story of what it means to care for others in a rapidly changing world.

What inspired you to write this book?

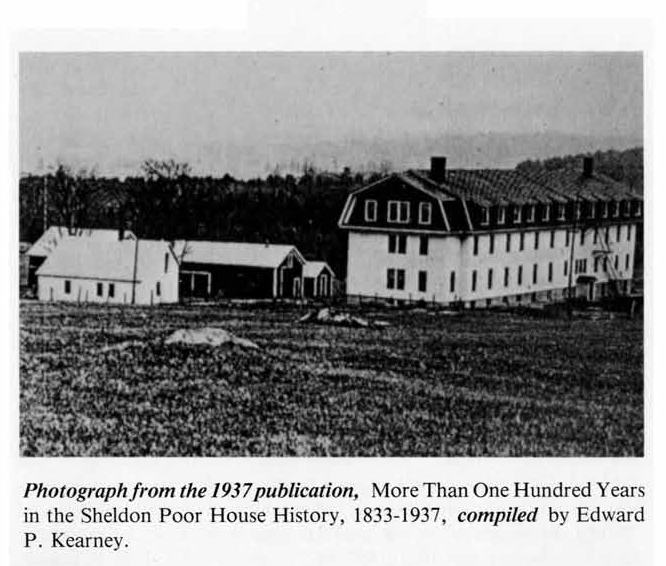

After finishing my debut novel, Telling Sonny, I didn’t intend to write another novel right away. I fully intended to return to the short story collection I’d been working on. Then I read an article in the Spring 1990 issue of Vermont Life Magazine: “Over the Hill to the Poor Farm: How an Era Ended Quietly on a Back Road in Sheldon Springs” by Steve Young. Seeing the photographs and reading the history of the place, I was struck by the fact that while I was growing up, I’d lived only seven miles from the Sheldon Poor Farm—yet I knew nothing about it. I’d been by the poorhouse building once in the early 1970s, but it didn’t register with me that it had ceased being a poorhouse only a few short years before. I had to know more. Around the time I read the Vermont Life article, I’d also been toying with the idea of a woman running away from her family with a blues musician, so I thought I’d combine the two ideas. It would be a lark, something fun before I went back to the short story collection. Little did I know where this idea would lead me!

Excerpt from The Weight of Snow & Regret:

January 1968

The cold winter sun hung low on the horizon, casting long shadows through the trees where once had stood clear meadow. Looking out the kitchen window as she peeled potatoes for supper, Hazel regretted the loss of the meadow—but when a meadow lost its usefulness, the forest would have its way and reclaim it.

The shadows lengthened. Hard winter had set in, a time of concern for the animals in the unheated barn and worry for her husband crossing the frozen dooryard in the dark to tend to them. Keeping up with the farm wore on him, now that he was in his sixties and there were no able-bodied men left with the wits needed to help him with the milking and the fields. Like it or not, Paul was showing his age.

As Hazel cut a bad spot from a potato, she thought she saw the bump and flash of headlights from a vehicle slowly making its way up the icy driveway. Looking more closely, she was surprised to see the Enosburg town constable’s LTD.

By 1968, new arrivals at the Sheldon Poor Farm were rare, just the occasional pitiful soul too infirm or senile for their families to bother with anymore. Even the derelicts no longer appeared at their door seeking a fresh start, only to drift into drink once more after a decent meal and a good delousing.

Hazel and Paul had seen so many of those old rounders come and go over the years. Buried a few, too, in the farm’s cemetery down the road. Each time Paul looked into an open grave, he pronounced its intended occupant a “poor bastard,” while Hazel murmured, “No mother’s son should come to such an end as this.”

What exciting project are you working on next?

My next project is a collection of short stories titled Enosburg Stories, set in the village where I grew up. Back when I was thinking about becoming a writer, I had a fantasy that I could become the Sherwood Anderson of Enosburg Falls, Vermont. So far, I don’t think anyone else has claimed that title!

When did you first consider yourself a writer?

I went to college and graduate school for creative writing, but I considered myself “aspiring” until I had a few publications in literary magazines.

Do you write full-time?

Yes, I write full-time. I retired from higher education five years sooner than I’d planned so that I could devote myself to my writing.

What’s your workday like?

I write in the morning and sometimes before I go to bed if bubbling ideas come to the surface. The rest of my day is spent on publication, marketing, promotion, and author platform activities.

What would you say is your interesting writing quirk?

Probably that my favorite part of the writing process is revision. When I first started writing, I couldn’t envision the story any other way than how I’d written it. It took me years to learn how to do it.

As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up?

As a child, I was very taken with National Geographic’s photographs of the Tutankhamen exhibit and Pompeii. I wanted to be an archeologist when I grew up and make these wondrous discoveries to bring the past to life. Then I learned that archeologists spend the majority of their time crouching in the hot sun sifting dirt through a sieve—and that was the end of my archeology ambitions.

Anything additional you want to share with the readers?

The Weight of Snow and Regret ended up having a timely social justice theme, which I did not intend when I began writing it.