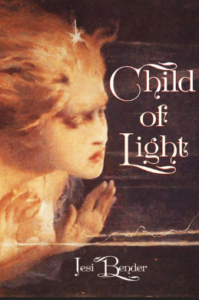

Historical author Jesi Bender chats with me today about her new experimental historical novel, Child of Light.

Bio:

Jesi Bender is an artist from Upstate New York. She is the author of the novel Child of Light (Whiskey Tit), the chapbook Dangerous Women (dancing girl press), the play Kinderkrankenhaus (Sagging Meniscus), and the novel The Book of the Last Word (Whiskey Tit). Her shorter work has appeared in Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Denver Quarterly, FENCE, and Sleepingfish, among others. The Brooklyn production of Kinderkrankenhaus was a top-three finalist for the BroadwayWorld’s Best Off-Broadway Play 2023. She also runs KERNPUNKT Press, a home for experimental work.

Welcome, Jesi. Please tell us about your current release.

Child of Light is experimental historical fiction and a queer Electra myth that explores the intersection of spiritualism and electricity from the perspective of a 13-year-old girl, Ambrétte Memenon. Set in Upstate New York in 1896, Ambrétte is drawn into a deep abyss of the unknown as she learns more about both death and the invisible pulse of the spirit.

What inspired you to write this book?

The origin for this whole story is a house on Genesee Street in Utica, NY that I love—a red brick, Romanesque Victorian with a huge turret and stained glass windows. I’d drive by ‘my house’ and marvel at it and knew I wanted to have a story centered around this beautiful but austere home. I love Utica, partly because it feels so haunted by its past with these looming relics of prosperity while many people today are struggling. As I did research about the house and the local history of Utica, I became really interested in the dichotomy between the surge of spiritualism and alternative spirituality happening across Central New York’s “Burned-over District” and the huge scientific advancements happening, most notably in electrical engineering and domestic lighting. These two elements seemed to be both opposites and yet somehow related, so I wanted to explore that further by having the protagonist’s mother embody Spiritualism and father embody electricity. So, Child of Light became a story about the tension and symbiosis inherent in the dualities of wealth and poverty, men and women, soul and mind, social mores and rebellion.

Excerpt from Child of Light:

Like raindrops caught in a spider’s web, a sheet of nebulous eyes keeps watch over the current that runs underneath the burned-over district, between Albany and the new Jerusalem in the West where lakes form fingers to hold that holy place aloft. It comes from within the earth, this pulsing, and the creatures conscious of its steady thrumming, though camouflaged by verdure or shadow or deep brown loam, maintain a constant vigilance.

Almost exactly halfway between these anchoring points is a small city whose native people originally gave it a name that meant ‘around the hill’. Now it is called Utica, after the ancient Phoenician city that married the Straits of Gibraltar to the Atlantic Ocean. Formed at the base of the Adirondack Mountains, Utica-around-the-hill grew from the marshy banks of the Mohawk River, a coulee that dips deep into the beating heart of an unseen power.

Power. Energy. The light that sparks a shower of tiny crystals. Electricity is often thought of as having been invented—but, of course, it wasn’t. It has existed as long as life itself. And, like life, we can only begin to imagine its beginning or predict its end. In the beginning was the word…

What exciting project are you working on next?

I’m wrapping up a folk horror novel about Grace Brown and starting research on a new work about the ‘Wobblies’, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

When did you first consider yourself a writer?

I’ve always been a reader and fell in love with many books throughout my childhood. But I started writing poetry seriously in college. Holding a print copy of the (now defunct) undergraduate poetry journal with my angry young girl poems about G-d and longing felt very ‘real’.

Do you write full-time? If so, what’s your workday like? If not, what do you do other than write and how do you find time to write?

I do not write full-time. I have been a librarian for over a decade and currently work in library IT, managing a group of developers who maintain our discovery system, websites, and other digital projects. I’m also a mom. So, I find time to write ‘in between’ everything – I’m not sure exactly how it happens. It’s always a small miracle to have sustained time to focus on writing. The one thing that helps me is that I am constantly ruminating on the story and on language, even when I’m unable to be write.

What would you say is your interesting writing quirk?

I do throw around a lot of dashes (-) and am still holding strong on to the double space.

As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up?

I wanted to be a cartoonist, because I liked to write and draw and I wanted to be funny. However, as I got older, I realized that I am very rarely funny on purpose, so I took a sharp turn towards death and sadness in my art.

Anything additional you want to share with the readers?

I am happy to talk to anyone about this project – you can contact me via my website. I’m trying to bring some experiments in form to the historical fiction folks and some history to the experimental folks. All of this is in the hope that we can be less rigid with writing ‘rules’ and embrace writing as an art form as equally as we’re willing to embrace it as a craft.