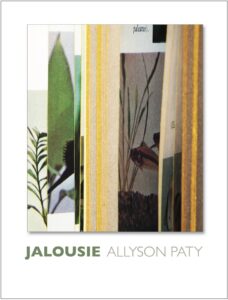

Poet Allyson Paty joins me today to chat about her new chapbook, Jalousie (Tupelo Press, 2025).

Bio:

Allyson Paty is the author of Jalousie (Tupelo Press, 2025), winner of the 2023 Berkshire Prize, and several chapbooks, most recently Five O’clock on the Shore (above/ground press, 2019). Recent publications include poems in Denver Quarterly and Denver Quarterly’s FIVES, Fence, Poetry, The Recluse, and The Yale Review, and nonfiction in The Baffler. A 2017 NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellow in Poetry and a participant in the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council’s 2017-2018 Workspace Program, Allyson Paty is co-founding editor of Singing Saw Press. She works and teaches at NYU Gallatin and with NYU’s Prison Education Program.

What do you enjoy most about writing poems?

I work slowly. Returning to a poem over a period of weeks, months, or even years, allows me to stay with ideas I can’t resolve or exhaust. But as language accretes over time, the original idea becomes lost in—or at least secondary to—shaping the material on the page. That shift is my favorite moment in the process.

Can you give us a little insight into a few of your poems – perhaps a couple of your favorites?

The title of the collection shares a title with one of the poems in the book. It’s the French word for “jealousy,” which in English denotes blinds or shutters made with horizontal slats whose angle can be adjusted for light, air, and privacy. The poem features two literal windows, and I wrote during the first Covid lockdown, when I was spending a lot of time indoors, gazing out. But I was also interested in windows as markers of distance, emphasizing the viewer’s position as apart from the scene on the other side. And I thought about various modes of looking from one place into a wholly other place, even figuratively—for example by reading ancient texts in translation or by dreaming. I decided to adopt this title for the book because attention to perspective itself runs through the collection. Many of the poems attend to making and reading images, whether formal images that exist outside of the poem (paintings, photographs), or a poem’s own ability to still and frame visual information, mostly through description. Poems such as “I Dreamed a Word That Meant a Break in the Weaving,” “Decade,” and “Verisimilitude” deal directly with visual vantages. Others, like “Love Poem” and “Self-Monument,” deal with the partial nature of representation and knowledge. Although there’s not much to do with jealousy as an emotion, I connect jealousy with a very tightly bound, even rigid, sense of self. There is a lot in the collection about the borders between the private and the public, examining where sensory information butts up against the social or historical to sound out the edges of a self.

What form are you inspired to write in the most? Why?

Jalousie is pretty formally restless. There are long poems, short poems, clipped lines, and lines that play with extension, lyric poems, narrative poems, and poems that operate like essays. There’s even a performance score. I think when I’m writing I’m often casting for a form that gets at a kind of logic or argument beneath the meaning of the words themselves. For example the longest poem in the book, “Premise,” uses only present perfect participles (having done X, having been Y…). The action of the poem just follows the speaker through a morning of no special consequence, but the grammar of the poem creates flattens time into an open, ahistorical “past.”

What type of project are you working on next?

I’m working on a manuscript that is in some ways a breakup book, and in some ways an extended work of ekphrasis. At the end of a long-term romantic relationship, as I navigated the impulse to parse what was happening, what had happened, etc., I found affinities with questions that have long interested me about narrative, representation, and figuration. Some of the artworks that come up in the book are Nam Jun Paik’s 1962 Zen for Head, the 15th century Noh play Ashikari (The Reed Cutter) by Zeami Motokiyo, three 18th century still-life paintings by Anna Maria Punz.

When did you first consider yourself a writer / poet?

One true answer would be since I learned to write, in childhood. Another true answer would be in 2009, when I was a senior in college. A friend started hosting weekly writing workshops at his apartment. That was my first experience of connecting with others socially through writing.

How do you research markets for your work, perhaps as some advice for not-yet-published poets?

At my job, I work with undergraduates, and when a student is interested in publication, I recommend that they pull out a book they admire that was published in the last few years, make a note of the press, turn to the back and look for the publications listed in the acknowledgements, and then to research the book publisher and the periodicals. If they can’t think of any books they admire from the past five years, I tell them to go to readings. Reading contemporary literature—especially from small, independent presses—is the most rewarding way to get a sense of what your work might fit in (or stand out). I also very much believe that the foundation good writing is good reading.

What would you say is your interesting writing quirk?

I write totally out of order. Not just poems—emails, essays, feedback on my students’ essays, even the responses to these questions! I always have to check to make sure I haven’t left a sentence dangling.

As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up?

My first dream job was to invent words for the dictionary. Discovering that no such job exists was a big disappointment. But then I wanted to be an olympic gymnast.

Links:

Website | Tupelo Press | Instagram