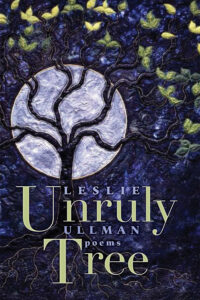

Poet Leslie Ullman is chatting with me about her new collection of poems, Unruly Tree.

Welcome, Leslie. Please tell us a little bit abour yourself.

I have published seven poetry collections, most recently Unruly Tree (University of New Mexico Press, 2024) and a hybrid book of craft essays, poems, and writing exercises titled Library of Small Happiness. A chapbook titled Self Portrait as Vanishing Act will be published by Lily Review Press in 2025. My awards include the Yale Series of Younger Poets Award, the Iowa Poetry Prize, the New Mexico/Arizona Book Award, and two NEA Fellowships. Professor Emerita at University of Texas-El Paso, where I spearheaded the Bilingual MFA Program, I remain on the faculty of the low-residency MFA Program at Vermont College of the Fine Arts. I also taught skiing for fifteen years at Taos Ski Valley which, astonishingly, was not so different from coaching writers in the motion of their own evolution. I live in Arroyo Seco, New Mexico.

What inspired you to write this book?

I have come to love having a “sequence” project in my life—but by that I mean, I have felt grounded by having a series of prompts, each of which forces me to leap into the unknown on terms not mine—this, as opposed to having to come up with ideas for poems before sitting down to write. I had just completed a project in which I had taken the last line of the previous poem to make it the title or first line of the next (this eventually became my fifth collection, The You That All Along Has Housed You, Nine Mile Press, 2019), and I was excited when a graduating student in the Vermont program distributed Brian Eno’s and Peter Schmidt’s 110 “Oblique Strategies” in her lecture on lists. At the time, I had never heard of Brian Eno (shame on me!) and felt as though I was reading rough translations from another language. None of the prompts made sense; thus, they struck me immediately as promising titles for poems I had no initial idea how I would write. If it’s helpful, I’m offering my preface to the collection:

Preface

In 1975 composer Brian Eno and artist Peter Schmidt created a list of 110 Oblique Strategies which they produced as a deck of cards, one strategy per card, to be drawn by an artist or composer wishing to be jolted out of a rut and into action. The project arose from the discovery that they approached their art in remarkably similar ways. For Eno, who survives Schmidt and has continued to give interviews on the subject as well as compose a significant body of innovative ambient music, the Strategies evolved from situations of “panic” when he felt creatively stuck in the middle of limited and expensive studio time. These situations, he recalled, “tended to make me quickly forget that there were…tangential ways of attacking a problem that were in many senses more interesting than the direct head-on approach.” The Strategies were designed to encourage lateral thinking—to help artists break through barriers via tangential routes and take themselves by surprise.

I was introduced to The Oblique Strategies as part of a handout at an MFA student’s graduation lecture on “lists.” The clipped, inverted grammar of most of the phrases read like literal translations from another language, reflecting syntax constructed from patterns of thought foreign to me. Although I knew otherwise, I chose to embrace that impression that the Strategies were half-digested, incomplete fragments whose linguistic origins were so distant as to provide me plenty of room for inventions of my own. In effect, I fell right in with what Eno and Schmidt intended—engagement with the mystifying challenge of each utterance. I decided to try using all 110 of them as titles and catalysts to poems, each time waiting out a period of resistance and sometimes outright paralysis until something broke through. Ultimately, I felt refreshed and free—to play, to write duds—and often I found myself exploring the literary, visual and musical arts from angles that had never occurred to me before.

The Strategies prompted me to re-visit loved paintings and research the painters themselves, to attend concerts where I not only absorbed the music but studied the gestures and facial expressions of the performers, to listen more deeply to jazz, electronic, and popular music, and observe my own experiences as maker of poems through a new lens. Sometimes I found myself treating the blank page as a musical score in which to manipulate margins and white space in ways new to my ear; in the process, I came to experience language as a more malleable, and more rhythmic medium than I had before. After all this play and exploration, I was sorry when after four years I got to the last of the Strategies, but I have retained something of lens they offered—holographic and ever-shifting.

I pared everything down and assembled this manuscript during the Pandemic and a proliferation of other disasters—mass shootings, police violence, infractions against Americans of color, and repeated attempts to undermine our country’s democracy, most of which remain in the headlines today. I would hope these poems offer, at least by suggestion, some reminder of that most interior and resilient of freedoms—the impulse to fully inhabit and bear witness to an inviolable inner life, an impulse that has persisted in humans throughout history even when shrouded, misunderstood, or denied by circumstance.

My thanks to Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt for the nourishment their quirky enterprise continues to provide.

What exciting project are you working on next?

Having published three sequence-related collections relatively recently, I’m now giving myself some time to experiment poem by poem and try out a new, sort of aphoristic approach to some of the new work. At first I felt unmoored without a sequence in mind, but it’s been interesting to give myself writing exercises as a point of departure and let each poem take me somewhere new, especially in terms of a voice and pacing that feel new to me. I’m not in a hurry to publish another book and don’t mind waiting to see which of 40 or new poems will be worth keeping and how the keepers might coalesce. In recent years I have enjoyed using the pressure of a poem-a-day project I do with two friends each August to help me generate a lot of new drafts in a short time, then using the ensuing months to revise and revise. As long as I have material to play with, I’m fine with taking things one poem at a time and not knowing where I’m going with the new work, though I wish it were a little less uneven!. Essentially then, my latest “project” is to just immerse myself in process, in patience, and see where I end up.

When did you first consider yourself a writer?

In college, when I took first a workshop in magazine writing, and then two poetry workshops. I fell totally in love with both genres. And decided I’d try to go into magazine writing and editing, while writing poetry on the side, which I did for three years before I decided to go for an MFA and devote myself to poetry. I applied to the Iowa Writers Workshop and got accepted. That led me to my career in teaching, something I had never anticipated wanting or being any good at. It turned out to be absolutely right for me.

Do you write full-time? If so, what’s your workday like? If not, what do you do other than write and how do you find time to write?

I like mornings best, though often a productive morning session makes it easier for me to go back to the work later in the day. I try to clear time first thing every morning to visit my work, and to not get too caught up in emails and other tasks, though I do this with mixed results. I find multi-tasking works for me, to a degree—open up a poem file and tinker awhile, then do something else and come back to it, flitting around it like a hummingbird around a feeder…. If I have student work to address, that takes precedence over everything, but that comes in small spurts and doesn’t interfere too much, overall. I also do something physical every day—a four-mile run or a bike ride or, now that it’s winter and I live near a great ski area, skiing four or five times a week. Some yoga in the warmer months. The physical things are a real pleasure for me and a good accompaniment to the writing. Oh, and when the Pandemic hit, I resumed a Transcendental Meditation practice I learned in the ‘80’s—this has helped in subtle ways, maybe in terms of helping me get out of my own way and trust that sentient waiting, rather than willpower, can lead to clarity.

What would you say is your interesting writing quirk?

I don’t know if this is a quirk, and I don’t know that it isn’t somewhat common among writers, but I’m surprised that while I dislike reading news and essays and other things on screen (which I do daily and doggedly)—and thus skim superficially in order to finish something and delete it—I love drafting my own work on a screen as well as engaging with my students’ work there. In those cases, I feel absorbed, content to hang out with the manuscript and converse with it, and in fact doing these things on screen helps me drop more deeply into them. I also find I can type fast enough to keep up with my thoughts. So composing on a screen is completely different for me than plain reading, and in fact, I have to re-train my brain to engage in “deep reading” by reading as many articles and books as I can in hard copy, with my back to the computer. On screen, I experience absorption and patience in dialoguing with my own and others’ work, but great impatience with any other reading there. What’s going on?

As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up?

A champion figure skater, then later a champion ski racer. I still, in late middle age, like to daydream about running gates on the World Cup circuit.