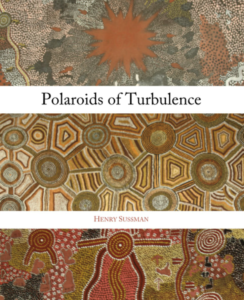

Poet Henry Sussman joins me today to chat about his new book, Polaroids of Turbulence.

Bio:

Henry Sussman is a critic and writer currently living in New York City. Trained in nineteenth and twentieth-century Euro-American Literatures and Critical Theory at Brandeis and Johns Hopkins, he has practiced poetry for decades as an alternative text-medium to fiction and discursive prose. Although interrupted with visiting stints, the major venues for his teaching were SUNY-Buffalo (Comparative Literature, 1978-2010) and Yale (German, 2002-17). Literacy, the interplay of media, and the theory and architecture of cultural systems have been, over recent decades, his primary preoccupations. Drawing their impetus from French theory and twentieth-century philosophy, the Frankfurt School, and psychoanalysis, his writings on literature have largely concentrated on Euro-American modernism and its austere aftermath. He has been the recipient of NEH Humanities (2), Rockefeller Foundation Humanities, and Fulbright Fellowships. Under their aegis, extended travel became possible. His most recent work of criticism is The Great Dismissal: Memoir of the Cultural Demolition Derby, 2015-22 (Bloomsbury Academic, 2023). October, 2023 saw the premier of his play, “Soirée at Walter Benjamin’s,” at the New York Theater Festival. Other of his critical works include Playful Intelligence: Digitizing Tradition (2014), Around the Book: Systems and Literacy (2011), The Aesthetic Contract (1997), and Afterimages of Modernity (1990). Polaroids of Turbulence is a debut volume of poetry.

Welcome, Henry. What do you enjoy most about writing poems?

Among so many factors: The intense mental concentration that the process demands; the unusually dense deployment of language and in the compositional product; attention devoted to the visual appearance of words as well as to their graphic placement and patterning on the page; opening the intense deliberation of writing to chance elements: e.g., outrageous rhymes, puns, and other marginal linkages and tenuous semantic associations; the special poetic potential inherent to deeply seeded introjections and outtake from dreams; finally, the opportunities for growth and discovery, the access to new possibilities invariably released in the interminable process of revision.

Can you give us a little insight into a few of your poems – perhaps a couple of your favorites?

Looking back, my poems, published and unpublished, fall into a number of very rough categories. Extended travel created multiple opportunities to compose poems of place. In general, these take on the task of summating a complex, riveting environment in a shorthand of the most vivid, trenchant details available. Also of staging an extended virtual feedback loop between observer and environment. Among these texts, my mind gravitates to “Bangkok,” “Genocide,” “Collective Dream of the Baseball Stadium,” and “Where U R.” A second portfolio of work to have emerged, particularly since the millennium, is poems responding to world events, such as the attacks of 9/11/01 and the volatile cloud chamber of contemporary U.S. politics. (I thoroughly sympathize with the tact and reticence that would preempt many a writer from venturing here; this admirable discretion, however, has not held me back.) Poems in this edgy direction readers might want to try out include “Incursions of the Real” (9/11), “Three Deer in a Development Near Harrisburg, PA” (climate change), “Atlas of Vanished Places” (COVID), and “Collateral Dommages,” “The Enchanted Isles,” and “Tweetings from the Great Leader” (the current U.S. political scene). A third sheaf of my poems is irreducibly ekphrastic, attempting to infuse my years in the classroom into encounters with artworks, some classical (“Where U R”), some situated in the media (“What Has Been,” “Yet Another Crime Mini-Series”). And finally, the almost inevitable autobiographical pieces, those loci where the traumas that make all of us human announced themselves in clipped, introjective outbursts of resonant verbal material: “Visits to Hometowns Never Inhabited,” “From Jefferson Hospital,” “Seder, Sussmans, 1954.”

What form are you inspired to write in the most? Why?

My poems invariably set out with epigrammatic phrases that simply occur to me. (Whether upon waking or as I walk around the city.) The inciting material is linguistic “ready-mades” produced by a roving eye in conjunction with the living environment–and also with sleep. The next few lines, in which I “set” these introjective phrases, will determine the form of the poem. The compositional process is inevitably a free one, but as my hardcore poetic material (or Stoff—German–or stuff) dictates where it wants to go, the poems often develop reasonably comparable stanzas. Since the millennium, a resonation between “hold-over lines,” situated at the right margin, and the body of the text, with its left-margin orientation, has become a telling feature of multiple poems (e.g. “À une passante”).

What type of project are you working on next?

I have been composing and refining an outrageous ekphrastic poem consisting of cantos devoted to my lifetime films and their directors since 2003. It is called “Screen Memories,” and it details my revisiting my all-time favorites, by the likes of Fellini, Truffaut, and Kurosawa, on an old SONY Trinitron with DVD in my Buffalo living room, 2003-08. Enhanced with movie close-ups and other stills, this would hopefully make for a visually striking volume of poetry. I have also completed a second volume of lyric poems, “Villages and Habitations,” a more explicitly autobiographical companion-piece to Polaroids of Turbulence.

When did you first consider yourself a writer / poet?

By contributing intermittently to “The Mirror” (Central High School, Philly, 1961-3). Also, by editing and supplying material for “Advent” (off-campus literary review, Central HS/Girls’ High, 1963-4).

How do you research markets for your work, perhaps as some advice for not-yet-published poets?

Publishing poetry at the present moment is for me a going public with an intermittent counter-practice spanning decades. In many respects, research on the potential outreach of my work was undertaken decades in advance. The writing I did in conjunction with the academic press was already trained on a literate readership with a demonstrated concern for the state and support of culture and the arts in the U.S. and beyond. In my poetry, I’ve had to struggle with some of the insularity and obscurity at times infused into disciplinary academic writing. Poems can and should speak to anyone motivated to read them. In the venture of publishing poetry, I’ve contended with the disadvantages as well as the advantages going hand in hand with my particular slant. It is the reader who will determine if I’ve succeeded.

As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up?

Ages 7-12: scientist; ages 12-15, writer; ages 15-17, psychiatrist.

Anything additional you want to share with the readers?

The sheer joy, at this moment in life, in encountering publishers such as Geoffrey Gatza of BlazeVOX, plus an amazing array of supporting characters (readers, publicists, reviewers) completely lit up in their mission of creating, disseminating, and diversifying literature. Both during the current season of high turbulence in media, technology, politics, and culture and for generations to come.