Poet Suzanne Mercury chats with me today about her newest book, Hive.

Bio:

Suzanne Mercury is the author of Hive (Lily Poetry Review and Press) as well as two chapbooks: Sassafracas (2018, Xexoxial Editions), and Hand to Earth (2019, Portable Press at Yo-Yo Labs). Her work has appeared in a variety of publications including SpoKe, Truck, Summer Stock, Bombay Gin, Sonora Review, and Hayden’s Ferry Review, as well as in the anthologies Let the Bucket Down and The Wisdoms of the Universes in a Single String of Letters. A graduate of Smith College and of Syracuse University’s MFA program in creative writing, she currently lives in Boston, where she keeps bees.

Welcome, Suzanne. What do you enjoy most about writing poems?

One of the things I love about writing poetry is that a poem can convey a great deal of meaning and feeling— hell, sometimes the wisdom of the universe— with very few words. I love the process of finding those words. I sometimes spend a crazy amount of time on poems that get shorter and shorter as I go along. I have some poems I have been writing for years.

When I write– well, when I write and things are going well– it really feels like I’m entering one of those houses described in faerie tales or found in dreams that are larger on the inside than they appear to be on the outside. The poem is an object or a place, filled with secrets. I love going to that place. It isn’t like anything else.

This is a really great question, btw.

Can you give us a little insight into a few of your poems – perhaps a couple of your favorites?

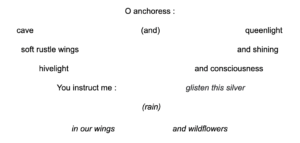

Hive is essentially one book-length poem, but I think many of its stanzas work as stand alone poems, particularly the more visual parts where I shape the poem to look, if not like a bee precisely, like a thing that flies:

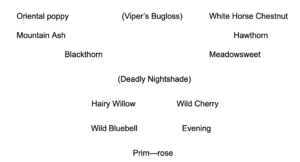

I also like this shaped stanza where I just name the plants the bee forages:

It took me forever to find that list because I needed to learn more about where my bees actually went to forage and what plants they like most. Beekeeping makes you highly aware of what grows wherever you are keeping the hive. You get to know the trees, grasses, and flowers very well after a time. It’s very intimate.

There are also a few places in Hive where I compare the hive to a library or an archive. This resonates for me because it is so true and you would never learn this until you actually keep a hive and care for it. You can read the comb after awhile and learn a great deal about where the girls have been. Also, there is nothing more wild than watching a brand new queen bee (who I named Inanna) crawl from her cell, newly born:

Hold me for me for just one moment

while Inanna

unfurls from her cell—

And then I wrote this, simply because it was true:

I’ve been stung twelve times today—

Just as an aside, before I became a beekeeper, I wrote a few poems about bees. All of those poems got recycled once I had some experience to draw from. Bees are just so very weird in so many ways that you can only discover slowly.

What form are you inspired to write in the most? Why?

I experiment a lot with form.

Hive is written in syllabics– it was a new experience for me, and very challenging! The syllabic formula I used is based on Agrippa’s Magical Square for Venus, which for me makes it a kind of spell, an incantation, a ritual. The square contains 49 numbers, and so Hive has 49 stanzas. Each stanza in the poem follows this numerical formula. When I finished, I read it to my bees and asked for their blessing. They didn’t sting me, so I am going to assume they liked it.

I think I really grew from the experience of composing this and sticking carefully to the form. It forced me to tighten up my process and cut even more from each part of the poem, to choose only what fit best and did the most work. Often it forced me to find new words because I absolutely had to have the right syllable count. It was like composing the music first, then creating the lyrics after.

What type of project are you working on next?

I thought I was going to continue using magical squares and syllabics, but I think I need a break from that, though I did get a good start on a poem about the Moon Rabbit, a mythical figure in East Asian folklore. Maybe I will get back to that someday, but probably without the syllabics.

I am currently working on a collection of much longer poems, some of which are about the photographer Anne Brigman, and one about environmental activist Julia Hill, who lived in a tree for 738 days in an act of civil disobedience to prevent the destruction of ecologically significant forests. I wrote a chapbook Hand to Earth (2018)which was mostly about trees, and I think the trees want me back.

When did you first consider yourself a writer / poet?

I was drawn to poetry pretty early in childhood, though back then the poems I knew best were songs, mostly folk songs, rock and roll, the torch songs my mother loved so much. During my teenage years, I found my way to Allen Ginsberg, Diane di Prima, Sylvia Plath, Helen Adam, Emily Dickinson. I was lucky to have a teacher in high school who was also a poet who egged me on. These were my doorways into poetry, and I think that was when I decided that yes, yes, I am a poet. During college poetry became a full-grown obsession. For me, poetry is a place of connection, where I can always be myself, where I find community– and I was sharp enough to know how important it is to have something like that. This world isn’t easy. I know that no matter what comes my way, nothing can erase this joy.

How do you research markets for your work, perhaps as some advice for not-yet-published poets?

Poets are often very solitary people in my experience, introverted, and very much at home with their own company and piles of books and all the time it takes to create. I well understand the temptation to go all hermit-like, but my best advice for new, younger, not-yet-published poets would be to seek out community. Go to readings, open mics, poetry slams, whatever speaks best to you. Introduce yourself! Connect. We need our ancestors, all those poets well-known or obscure who came before us, but we also need community and friends. Connect. LEt yourself get lost in all of those wonderful conversations, and never forget how important they are.

As for researching markets for your work, there are so many resources out there, but again, you are going to learn the most from your community. I’ve done well by just listening to the many people I’ve met who are more organized and resourceful than I am. One big thing, though, that I would urge: if you hear about a magazine that sounds like it might be a good place for your work, buy a copy first and get familiar. Send your work to places that really are a good fit for what you do. It sounds obvious, but a lot of people don’t do this.

What would you say is your interesting writing quirk?

Many of my poems have a visual component— how it is shaped on the page is important to me. But that visual side of things is also very aural— where I break the line or add in space corresponds to how I read the poem, how it sounds to me. So composing is a very physical experience. I write a little, then I read what I have written out loud, or sing and walk around the room with the words.

As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up?

A ballerina, of course! Didn’t we all? I trained in ballet for about ten years until foot injuries got in my way. I also figured out that I probably did not have the chops to be a professional dancer. So my other interests led me to journalism. I thought about becoming a dance journalist at one point, encouraged by my dance teachers in college. (Hmmmmm… was this their way of saying I was not a very good dancer?) Then I wandered into poetry.

Anything additional you want to share with the readers?

I love you all! Come to the open mic! Read and write like crazy and have faith in yourself. It might feel like jumping into an icy swimming pool at first, but I assure you the water is splendid.