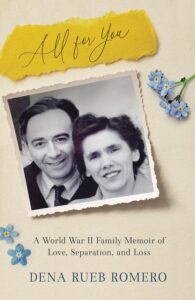

Writer Dena Rueb Romero chats with me today about her memoir, All for You: A World War II Family Memoir of Love, Separation and Loss.

Bio:

Dena Rueb Romero grew up in Hanover, New Hampshire, the daughter of a Lutheran mother and a Jewish father, both refugees from Nazi Germany. She graduated from Brandeis University and received an MA in English from the University of Virginia and an MSW from Boston College Graduate School of Social Work. Her previous publications include Gretel’s Albums, a collaborative bilingual internet project with researcher Bernhild Voegel (www.birdstage.net/kleeblatt), and an essay about German citizenship in A Place They Called Home: Reclaiming Citizenship, Stories of a New Jewish Return to Germany. All for You is her first full-length book. Dena still lives in Hanover, where she sings in a women’s chorus and volunteers at a daycare center and with an organization supporting refugees and asylum seekers.

Welcome, Dena. Please tell us about your current release.

All for You is the story of my parents and my grandparents. It begins in a small Rhineland village before Hitler and tells how the Third Reich affected my Jewish father, his family, and my Lutheran mother. Hitler’s Racial Purity laws made my parents’ relationship illegal, and they had to meet in secret. The story follows my father to New York and my mother to England, the outbreak of war in 1939, and my father’s life as a refugee in a small New England college town as he tried to save his family and to bring my mother over from England so they could marry.

What inspired you to write this book?

The primary catalyst for this book was the discovery of a box of letters in my parents’ house. The letters were from my Jewish grandparents, copies of my father’s replies to them, and love letters between my father and my mother. I always believed that my parents’ story was one that needed to be told, and the letters, the voices of people living through extraordinarily challenging times, prompted me to bring them to life.

Excerpt from All for You:

From Chapter 5, Upheaval (1933):

For Germans, Heimat – the place where you were born and raised – was more than its literal translation of “homeland.” It was where you felt secure, where your roots reached back for generations, where you belonged. To leave your Heimat meant losing the life you were making, your identity, and yourself. It meant acknowledging that your version of Heimat did not match reality.

What exciting project are you working on next?

I have a busy and active life so I haven’t started any new projects yet. I would, however, like to write a piece about Friedelind Wagner, granddaughter of composer Richard Wagner, whom my family met by chance at an airport in Paris and befriended. I would like to research the Jewish families who hired my mother, a trained children’s nurse, to look after their children. Finally, I want to tell a related family story about an orphaned German boy who survived the war as a hidden child in Belgium.

When did you first consider yourself a writer?

That’s an interesting question. I would reframe it to say “when will you consider yourself a writer?” My answer: I will consider myself a writer when my book comes out, when I do the first public event, and there is interest in reading my book.

Do you write full-time? If so, what’s your workday like? If not, what do you do other than write and how do you find time to write?

When I worked full-time, I could write only in the summer when my schedule was lighter. Retirement allowed me to prioritize writing my book. Now my focus is getting the book out to the public since the reason for the book was to share my family story. I am still in a writing group and occasionally write a 5-8 page piece to read when we meet.

Other than write, I volunteer at a daycare once a week because I love babies, I sing in a woman’s chorus and take singing lessons, and I am a member of an interfaith local group advocating for solutions to the housing crisis in our area and volunteer with an organization supporting refugees and asylum seekers.

What would you say is your interesting writing quirk?

A member of my writing group says that my sentence structures are German; another says I use a lot of participles. I love details because they establish something about a person or a place, and I resist cutting any of them out. I have learned, however, that often my writing is better and stronger when I cut the extra details.

As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up?

First, I wanted to be a ballerina until I realized I didn’t have a ballerina’s body. Next, I wanted to be a doctor like Albert Schweitzer which later morphed into being a social worker which I did as a profession.

Anything additional you want to share with the readers?

In 2007, I applied for and received German citizenship. Some people might say “why in the world, after everything that happened in Germany, would you want to be German?” I answer that my father believed in having options. Perhaps, if he had had more options, things might have turned out differently.

Links:

Facebook