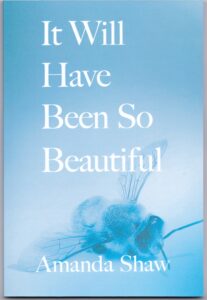

Poet Amanda Shaw chats with me today about her new collection, It Will Have Been So Beautiful.

Bio:

Amanda Shaw is a poet, editor, and teacher who currently serves as book review editor at Lily Poetry Review. A graduate of Warren Wilson MFA Program for Writers, she has taught language and literature at all levels for over 25 years. Although she’s lived in many different cities, states, and countries, she currently divides her time between New England and Washington, DC. Shaw’s poems probe language’s capacities in the hope that art might move us to a deeper commitment to life in all its forms. Her debut collection, It Will Have Been So Beautiful (Lily Poetry Review Books) implores us to consider what “home” means, particularly in the midst of an ever-worsening climate emergency.

Welcome, Amanda. What do you enjoy most about writing poems?

I used to try to write stories, but found they had two many words—I could write volumes and say the same thing less elegantly.

I lived in Rome for a time and spent a lot of it lost in the city’s narrow streets. When you ask Italians for directions, you unintentionally tap into their love of language. They’ll talk to you about all the landmarks you’ll pass and the rich history of each of them for several minutes, but really they are just telling you to go straight. It’s one of the most charming elements of living in Italy, but when you don’t speak the language you are bewildered and generally no better off in terms of finding your destination. I think my head works this way. Poetry is the best way to slow down and process all of the background noise by having to choose carefully among the words in my overstuffed head. Whittling down experience to as few words as possible keeps me honest.

Can you give us a little insight into a few of your poems – perhaps a couple of your favorites?

Because of my love of the natural world, I see the three “These Mountains” poems in the collection as a kind of spine. I was blown away the first time I witnessed the scale and blinding brightness of the Alps. Being in another part of the world changed the way I understood time, and the rapid shrinking of the glaciers since I first encountered them has been, unfortunately, a way of measuring climate change in real time.

In a collection that is so much about place and time, it seemed right to organize it in terms of the trajectory and geography of my life. The first poems in the book are set in Michigan, Switzerland, and Rome, and New Hampshire where I spent my early childhood.

My work becomes more overtly feminist as I age, so several of the shorter poems that appear in the last two sections have a more defiant note (“First Moon Out,” “Past Perfect.”) And my love for my husband and the children in my family comes out more prominently in the later poems.

I was trying to end the book with a sense of why art and love can redeem the losses we continue to sustain, so the final poem, “Where We Are,” speaks to that impulse.

What form are you inspired to write in the most? Why?

I start with a huge mess of language and associations and then see if I can get that down to a sonnet, then build back out from there.

What type of project are you working on next?

I’m working on a series of poems set in museums, usually starting with a particular painting, but they aren’t traditional ekphrastics. They’re more about the ways we experience art via the text on the wall and the “fame” of the artist, which is honestly kind of surreal–it’s such a mediated way to experience an artist’s work.

Two of the poems that didn’t make it into the book are called, respectively, “In the Musee D’Orsay” and “In the Museum of American Art.” They include visitors pausing in front of individual pieces–noting the little things viewers say to one another as they’re looking. It reveals so much about art’s place in our culture.

Last month, after AWP, I went to the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City. There was a woman, probably in her late 70s, sitting on the bench in front of a portrait of St John the Baptist by Caravaggio. Because this is a masterpiece of the collection, it tends to go out on loan for special exhibitions. She told me, “I like to check in on him from time to time. I miss him when he is gone.” I’m working on a poem about that right now.

When did you first consider yourself a writer / poet?

As a kid, I would dictate stories to my mom. The first masterpiece survives, entitled “The Prettiest Princess.” I was very influenced by the books my mom and I were reading. (See below: rhinoceros tamer.) The first “published” story came in a 1st-grade class anthology, about a whale and a sailor making friends. This probably guaranteed my love of Moby Dick.

It wasn’t until I began to teach poetry to 13- and 14-year-olds that I started writing my own, having witnessed what the genre did for them. Random lines from poems I was teaching (and whole speeches from Macbeth) became earworms. Despite having no time to write, I began to jot down rhymes, echoes, and “found language” in my notebook, which became poems. They were very pared back and sonically dense, but not terribly interesting. I’m not much of a minimalist, so the first finished poems didn’t emerge until I let myself go a little long.

How do you research markets for your work, perhaps as some advice for not-yet-published poets?

That is the most difficult part about being a writer, by far. It takes a thick skin to endure being rejected over and over again, especially when your work is so personal. My husband initially offered to submit my poems to reviews, but he found it really challenging to figure out which journals might be most receptive to my work. The best advice that was ever given to me—and I can’t say that I’ve followed it—is to submit a poem as soon as it is finished and move on to the next one. It’s kind of an “out of sight, out of mind” thing. Once the poem is out there, floating around, you don’t think about it as much, it loses some of what makes it so precious. I would also strongly recommend taking workshops, both as a motivation to keep writing, but also as a way to test poems and create a cohesive body of work.

Since this is my first collection, I’m very new to this–I was lucky to have my manuscript get picked up very quickly. In terms of growing an audience, however, teaming up with other writers and promoting one another’s work is a great strategy for getting your name out there. Open mics are a good way to start if you’re not already part of your local writing scene. Finding community with other writers is a process that expands exponentially.

What would you say is your interesting writing quirk?

The way I will announce to strangers that they’ve said something that belongs in a poem. For example, I was talking to a Bahamian woman in a store and we wound up sharing photos on our cell phones. At a certain point, after she’d looked at a number of mine, she said “Your family doesn’t lie,” meaning that you can see the resemblance, and I was like, oh! That’s a poem. Sometimes people look at me like I’m a little weird, and then I explain what I do, and that turns into a whole other conversation. In which it becomes clear to them that I am a little weird.

As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up?

At various times, a doctor, a fireman, a queen, an astronaut, a ballet dancer, and for a few weeks a rhinoceros tamer. I was naturally a teacher, being rather bossy, so that decision probably made itself. At the risk of being glib, particularly in the case of firefighters, teaching may very well be the hardest of all of those jobs, since you’re doing it all at once (metaphorically, of course).

Anything additional you want to share with the readers?

Just generally, for people who don’t read it regularly, poetry takes a lot of patience. Good poems reward you with each re-reading, as the meaning builds up in layers. You need to trust your instincts and enjoy the images, not worrying about whether you “understand.” And writers need to trust that the audience is going to connect without too much explaining.

I’d love for people to see this book as a story, though it’s told in intense flashes and moves around a lot. The poems are chapters to spend time with, and an 80-page book of poems is the equivalent of a 300-page novel in many ways.

I want to share what I’ve lived, but getting at the truth of that requires taking a certain angle in, then letting the poem be about whatever it wants to be about. I use a lot of references, but I’m not trying to make myself harder to read. I hope people will be interested enough to look things up online if they don’t recognize something, but you also shouldn’t need to in order to enjoy the sounds and images. I’m often just trying to open my mind to readers and say “Come in, if you dare. I promise you’re welcome.”

Links:

Website | Instagram | Facebook | Lily Poetry Review