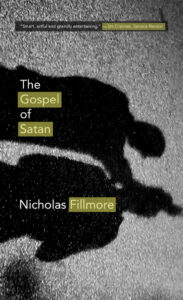

Novelist Nicholas Fillmore joins me today to chat about his new literary fiction, The Gospel of Satan.

Bio:

Nicholas Fillmore is the author of The Gospel of Satan, a novella, and Smuggler, an IndieReader Discovery Award-winning memoir.

Fillmore attended the graduate writing program at University of New Hampshire, was a finalist for the Juniper Prize in poetry and co-founded and published SQUiD magazine in Provincetown, MA.

He is currently working on Sins of Our Fathers, a novel, and The Genteel Pleasure of Anonymity, new and selected poems.

Welcome, Nicholas. Please tell us about your current release.

The Gospel of Satan is a retelling of the Gospels by Satan … as dramatic, historical, and philosophical corrective and exploration….

As down payment on a human soul, the Devil agrees to tell the story of Jesus, whom he’s taken up with on the Road to Jerusalem—long before any temptation scene. It seems the two have much in common. Jesus doesn’t particularly want to be crucified, nor the Devil to be vilified for all time.

On a deeper, philosophical level, the two are united in their opposition to the hegemony God exerts over all things: specifically, the Pauline construction placed on Jesus actions—everything Jesus does becomes miraculous—and the Devil’s “ontological dependance” on God: whatever he undertakes is turned to God’s greater glory. The problem, for all of us—God, the Devil and man—is this heavy hand of God deprives everyone of free will in the end.

(The irony, then, is Jesus crucifixion serves not to reconcile man with God, as the conventional wisdom states but, conversely, as an action taken up freely by Jesus, it would reconcile God with man, restoring that notion of free will that justifies human suffering….)

Of course the main action of the story is each character’s daily struggle to arrive at some predestined end by his own logic. E.g.:

The Devil it was, then, who went with Jesus, querying him along the way.

“Man’s soul, you say?”

“Does that seem strange?”

“A tad hyperbolic, don’t you think?”

“A figure of speech.”

“You figure?”

“I reckon.”

“Ah, now there’s la difference.”

“Not mine; man’s—reckoning, I mean.”

“And you the reckoner?”

“Whatever reckoning is man’s alone.”

“Now that seems strange.”

“You like to banter. Let me be plain. I would reconcile man with God….”

“Not G-d with man? who seems to have shifted the contractual language of late.”

“Man with God, God with man, either way.”

“Oh, no. Think on it.”

“Obviously, if we’re being Aristotelian about it, man, having transgressed G-d’s will, would be in need of reconciliation with God; God, in his infinite mercy, seeks to reconcile himself with man.”

“I don’t like it.”

“What?”

“All this G-d-talk. What know ye of G-d?”

“Nothing.”

“How, then, come you to speak for G-d? How does some little pischer carpenter who appeared out of nowhere presume to arbitrate matters of heaven and earth?”

“I don’t know.”

“I’m satisfied with that, for I confess it is a great mystery to me whence come and whence go such prodigies as thee, who arrive singing full-throated. Yet you’re not so young anymore.”

“My time is coming.”

“Yes, the world’s hungry, and those who inhabit must step aside or give themselves over to matriphagy. Isn’t that so?”

“Oh, you’re making my head spin!”

“Yes, the world’s a web with a fat black spider at its center.”

“Methinks it’s many webs; yet haven’t we somewhere to be? These country affairs have dulled my senses.”

“Not yet.”

“Yes, I know the prophecies. I know that man must have salt with his bread, wine with his meat. Truth be told, I don’t care about any of it. I only wanted to live my life, yet find each year that I’ve made another concession. There shall be no more concessions. My course is set. I shall run with the wind that is with me or tack against that which is before, giving it no more thought than the weather. If it please fate, let it commend me; if displease, tear asunder. Let the opinions of God and man be as air inside a balloon.”

“Bully.”

“Yes.”

“This course that you’ve set upon, then?”

“I once said ‘man’s soul,’ not knowing what that is; might also say his heart, not knowing that either … but my own. Mine own! which I know as an infant knows its mother’s voice. My own, which I heard calling to me at birth.”

“Every fool trusts his heart.”

“But if that heart be true?”

“Let’s test it….”

What inspired you to write this book?

“The argument” of this book probably took hold of me a long time ago, first in some inchoate way as an altar boy backstage before mass; later as an undergraduate reading Paradise Lost with Andrew Harvey and finding the idea that all one’s actions only play into a larger design deeply hateful; later still as an inmate in federal prison struggling to reconcile my own actions with the law. Gospel is an attempt to free those passions from the bonds of faith and to affirm (perhaps) a deeper, human truth.

What exciting project are you working on next?

It’s funny: the last time we did an interview, after I’d written Smuggler, I was working on Sins of Our Fathers. Then the Gospel intervened at some point. I think I’d reached a point of emotional exhaustion writing about all that family stuff, and swerved to Gospel, which I wrote really quickly, in about a year or so, relying on all that unconscious material mentioned above. Now I’m back on Sins. And so, again:

I’m currently working a book called Sins of Our Fathers, which takes as its point of departure a story my father tells of how he returned from two years in the service to find a note taped to the front door: “moved.” That’s something of an exaggeration. My grandparents moved out of state some time after he got back. But the poetic truth, the feeling of abandonment conveyed by the note on the door, (as well as the conceit of self-made man) was compelling. And I decided to construct a story around that moment. (Not a very good elevator pitch, I’m afraid.) That elaboration by my father, though, suggested a method, or rather gave me permission, to reconstruct events around available clues, personalities, hunches. I guess I’d call this personal historical fiction. It’s led me into some interesting places: following my grandfather on a drinking jag, for instance, and encouraged me to enlarge the received picture of our family history.

When did you first consider yourself a writer?

Freshman year in college, banging away on my Smith Corona late at night on a term paper after everyone else had abandoned campus for Christmas break. I felt a union of physical and intellectual energies akin to horse and rider.

Do you write full-time? If so, what’s your workday like? If not, what do you do other than write and how do you find time to write?

Well, I write a lot of the time, but I haven’t quit my day job(s), which currently consists of bartending in Waikiki at the Genius Lounge and Sake Bar. I mean, as long as you’re suffering, you may as well be glamorous, right? Actually, there are some potential changes on the horizon, and I may find myself adjunct teaching back in Boston at some point. We’ll see.

What would you say is your interesting writing quirk?

I have a polished egg-shaped stone on my desk that I habitually spin around and around.

As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up?

A kung fu master or a priest.

Anything additional you want to share with the readers?

Don’t sweat the big stuff. “The Devil’s in the details,” as they say.

Links:

Book Trailer | Website | Instagram | Facebook | Pinterest | YouTube | Mastadon | Goodreads