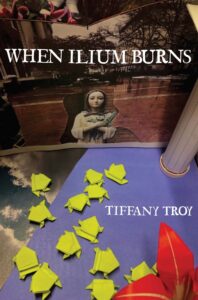

Today’s special guest is poet Tiffany Troy. We’re chatting about her new chapbook, When Ilium Burns.

Today’s special guest is poet Tiffany Troy. We’re chatting about her new chapbook, When Ilium Burns.

Bio:

Tiffany Troy is a critic, translator, and poet. Her reviews and interviews of emerging and established voices are published in The Adroit Journal, The Cortland Review, The Los Angeles Review, EcoTheo Review, Heavy Feather Review, and Tupelo Quarterly, where she serves as Managing Editor.

What do you enjoy most about writing poems?

What I enjoy most about writing poems is following a character’s arc in reaching an epiphany. That epiphany more often than not does not resolve the underlying conflict, for want of power. Nevertheless, it sheds light upon the journey as an experience worthy of our consideration or contemplation.

For instance, in “Thank You Card,” the Nurse is a kind of Sisyphus, condemned to fail in her attempt. Her “crime” is that all she believed in–in this case the healthcare system–turned out to be a sham. There is a way in which the gaslighting of a bureaucratic system can be compared to rolling a stone up a steep hill, repeatedly. Notwithstanding the “vain duplicity” of her supervisor, an epiphany of sorts is nevertheless reached with the final scene. I hope the reader can see that the world the Nurse loves is real, and her love in the patients is real, and be touched.

Ultimately, I write towards community. For me, it’s important to show that there are individuals like the Nurse everywhere around us. Just because we might not be heard—or seen—as the “right” kind, like Clarence Darrow perhaps we are not truly alone when we listen to our footsteps. Perhaps even with all the windows shut against us, we can take solace in fighting for what’s right.

Can you give us a little insight into a few of your poems – perhaps a couple of your favorites?

Of course! One sure way into the poems in When Ilium Burns is understanding the nuances in the character’s perception of their identities which the poet clues the reader into.

“Little Maria Wants to Take a Nap,” for example, is one of my favorites. It is a persona poem spoken from the voice of Maria Goretti, a Catholic martyr, who also features on the cover of the chapbook. Recently, I’ve been thinking through the idea of the diminutive, and why it is it’s “Little Maria” like the “little lamb” or “Baby Tiger.” Ultimately, I think what is kawaii (or cute) is sly because it of course in some ways affirm the idea of the character herself—or of the Asian identity—as being diminutive and derivative. But I would like to think beyond the cuteness is a sincerity, what Donald Revell calls the havoc at the heart of piety.

I feel the collection tries to center that cuteness as an integral part of the character’s identity (how she perceives herself through how she is perceived) and center that in the pageantry of depression and despair. That is to say, I find the heroism in Little Maria isn’t in her superpowers, but in her looking to and seeing beyond the fourteen neon green frogs. The fourteen neon green frogs allude to the number of lines and the poetic turn in a sonnet, the neon lights of Flushing in the rain, and the Mark Twain quote: “if the first thing you do in the morning is eat a live frog, you can go through the rest of the day knowing the worst is behind you.” It recasts Little Maria in a modern setting, held to and biding time against authority.

“Holy Saturday” was written on Holy Saturday. It draws from the occasion; it is a poem about the emotional state of falling into the abyss, but perhaps without that certainty of triumphal return. As in some other poems in the chapbook, “Holy Saturday” is about surviving in what Cyrus Cassells calls the “soul-crushing capitalist zeitgeist,” which I find so true. The cockroach to be exterminated recalls Kafka’s Metamorphosis (of the self as deplorable, of self as inescapable, and that misanthropist claustrophobia) and the way the protagonist sees herself given her identity. In turn, it is keyed back to the collection which thinks through intergenerational devotion in all its myriad form.

“Cardiogram” is a poem about being lost. Because of that, you’ll see that phrases float on the page. The poem mourns what is lost by paying tribute to the tenacity of life: Sinead’s “Troy” is definitely one of my favorite songs and it contains a reference to “phoenix from the flames,” as well as the ubiquitous “Welcome Back, New York!” MTA sign. This motif of the second coming–of the burning Ilium–which is condemned to burn recurs throughout the collection. I remember being so moved by Pico della Mirandola’s “Oration on the Dignity of Man.” And isn’t that power–to through one’s agency–rise to heaven or fall to the abyss, or even that perception of power, so poignant?

What form are you inspired to write in the most? Why?

Most poems in When Ilium Burns take their form (couplets, quatrains, or a more divergent form) based on the state the character is in. (What a lark! What a plunge!) The poems break forms the way people break code, the way at very abyss of sadness, speech breaks down into thought, and words themselves become truncated, staccatos.

Recently, the form I am inspired to write in the most is the modified quatrain form, whereby the second and fourth line is indented. There is something beautiful about this modified quatrain, visually, that allows for a different kind of complexity and variation in diction and thought to come out. It’s like being dressed up but instead of speaking to an audience, it’s like the soul of the character speaking to the character, with a kind of formal distance with a kind of mellowed-out rhetoric and high lyricism. That of course, is allowed for by the long poetic line, per Vijay Seshadri, who compares the long poetic line a space for more complexity in philosophical discourse. But I think the verse form (as opposed to the poetic prose block)—by allowing the poet the space to take a breadth—also allows for a slowing down—in contradistinction with the rapacity of the prose poem paragraph.

What type of project are you working on next?

I am working towards a book of poems called Jurisdiction, a castle in the sky featuring characters living the contemporary American professional life. What are the characters’ turfs, physical geographical demarcations of their limitations? And how might they seek to move beyond that, whether by stealth or otherwise? Besides that, I am very excited to speak with poets and writers about their work in my role as an interviewer. I love to build and give back to the writing community which has raised me up to where I am now.

When did you first consider yourself a writer / poet?

In high school a blue moon ago, after writing a canto after Dante’s Inferno, and receiving an A++ with a pikachu in Modern European Literature with Dr. Emily Moore.

How do you research markets for your work, perhaps as some advice for not-yet-published poets?

A poet I hugely admire, Sean Thomas Dougherty, once Tweeted about wanting to not publish, and just focus on the poetry. I feel that’s so true. I feel strongly that poetry—regardless of style or form—should be taken at their face value. Read widely, talk with poets, and write! Then submit when you feel you are ready, you never know what might strike the fancy of an editor on the other side of Submittable or an email.

What would you say is your interesting writing quirk?

I am maximalist in approach: and it probably isn’t surprising that some idiosyncrasies of my characters that made its way into the collection, like a perhaps overly detailed Burger King order!! When I go deep, I can go really deep.

As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up?

What nobler profession is there than being chained to the bottom of the sea? In all earnestness, even as a girl I had wanted to be just like my parents when I grew up. I saw my parents and wanted to change the world into a better place.

Thanks for being here today, Tiffany!