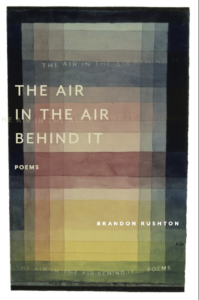

Poet Brandon Rushton joins me today to chat about his new collection, The Air in the Air Behind It.

Poet Brandon Rushton joins me today to chat about his new collection, The Air in the Air Behind It.

Bio:

Brandon Rushton is the author of The Air in the Air Behind It (Tupelo Press, September 2022), selected by Bin Ramke for the 2020 Berkshire Prize. He was born and raised in Michigan. A finalist for the National Poetry Series and the American Poetry Review / Honickman Book Prize, his individual poems have received awards from Gulf Coast and Ninth Letter and appear widely in publications like The Southern Review, Denver Quarterly, Pleiades, Bennington Review, and Passages North. His essays on environment and place appear in Alaska Quarterly Review, Terrain.org, the critical anthology, A Field Guide to the Poetry of Theodore Roethke (Ohio University Press, 2020), and have been listed as notable by Best American Essays. He co-founded the non-profit poetry outfit Oxidant | Engine and, after earning his MFA from the University of South Carolina, joined the writing faculty at the College of Charleston. In the fall of 2020, he began as a Visiting Professor of Writing at Grand Valley State University in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

What do you enjoy most about writing poems?

The process. Being perpetually in the middle of a poem. Having that thing to sit down with, to think and work through. To be tuned in to the momentum of language.

Can you give us a little insight into a few of your poems – perhaps a couple of your favorites?

I’ll talk about two poems that really opened this book up to me, made me see it as a project and as a new direction for my work. The first is the opening poem “Milankovitch Cycles”. Toward the end of the summer of 2016 I was immersed in – and in awe of – Richard Manning’s biological history of the heartland: the 1995 book, Grassland: The History, Biology, Politics, and Promise of the American Prairie. In that book, he discusses the scientific term “Milankovitch Cycles,” which refers to the eccentric orbital patterns of planet earth and the effects those cycles have on the climate. The cycles are named after the Serbian geophysicist Milutin Milankovic who theorized their patterning in the 1920s. I was drawn to the term and I knew I wanted to use it as a title, at some point. I didn’t know it at the time, but that chance encounter – my interaction with that term – would be responsible for the book’s opening poem and carry a lot of its momentum and structural weight.

The second poem is “Roll Call”. Having moved away from Michigan in my early twenties, I returned each summer and couch surfed and slept on my friends’ floors. It was an easy way to make sure I saw everybody I loved. And, it made my summers really interesting. One summer, while visiting my friends Nick & Erica, after a long night of porch sitting and catching up, I woke one morning to their daughter running through the house, running through the light. That image, the love I felt that summer, led to the writing of “Roll Call,” which made me consider the roll longer poems would play in the collection.

What form are you inspired to write in the most? Why?

For this book, I worked primarily with long poems, using indented tercets. The possibilities created by the shape – and the opportunities for enjambment – made the form feel the most open to association and improvisation. I think it’s the perfect form, for me at least, for defamiliarization.

What type of project are you working on next?

A collection of poems about motion.

When did you first consider yourself a writer / poet?

I think during a college communications class. I couldn’t pay attention and I used the entire class time each week to write poems while the professor lectured. I did bad in the class, but it made me realize I wanted to spend my time writing poems.

How do you research markets for your work, perhaps as some advice for not-yet-published poets?

I familiarize myself with the work literary journals and presses publish. I read the “acknowledgments” page of poets and writers whose work I admire to see other venues where their work has appeared. I tend to assume if I like a writer, I’ll also like the publications they’re interested in. For a solid list of notable publications, I always recommend beginning poets check out NewPages.com.

What would you say is your interesting writing quirk?

If I can’t move forward in a piece, I often go for a run. There’s something about the body and landscape in motion, the blending and smearing of scenes and thoughts that smudge up my mind in a similarly productive manner.

As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up?

An astronaut or a storm chaser. I blame the mid-90s, though. During that time, I watched a lot of Apollo 13 and a lot of the quintessential 20th century cinematic masterpiece: Twister.

Anything additional you want to share with the readers?

The Air in the Air Behind It fuses together two landscapes, two regions that mean a lot to me: Michigan and South Carolina. Focusing on these two locations allowed for mutations in scenery and language. In many ways, I consider this book to have been written in a perpetual state of bafflement. Most of the “mutations” I experienced while living in SC were those related to the weather: annual hurricanes, daily tidal floods, and sudden heat waves. I was dumbstruck – in tandem with the weather – by the sense of proliferation and development, the collective human desire not only to make, but also to destroy and make again. I scratched my head constantly at human behavior, at the patterns of people (including my own) and the sometimes inexplicable, but amazing reasons we do the things we do. The Air in the Air Behind It is a book about human and weather-related turbulence, how those two turbulences – at times – coalesce. I wanted to write about the strangeness of the days I walked through, the water I drove through, the incessant folding and unfolding of events, and the sudden transmogrification of things that felt so fixed and certain. Doing so resulted in a book that experiments with concepts of symmetry, balance, proliferation, dissolution, disillusion, and endurance in an effort to represent the historical and climatic magnitude of the days in which we live.

Links:

Website | Tupelo Press