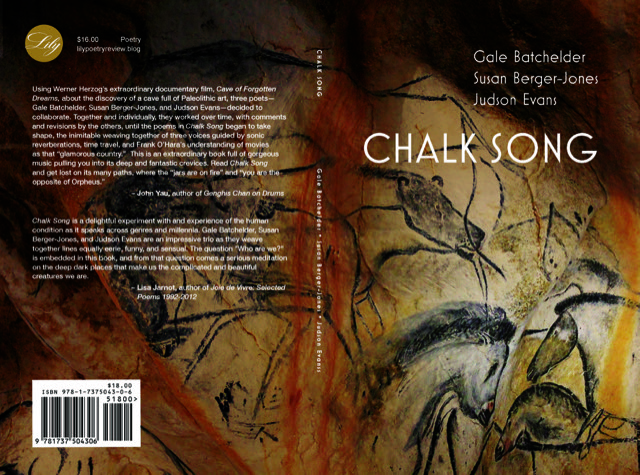

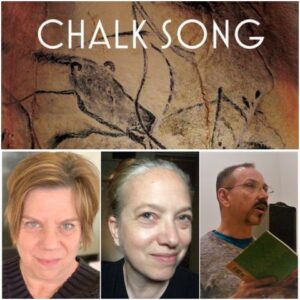

Multiple creative individuals are squeezed in under the spotlight today. I’m happy to introduce you to poets Susan Berger Jones, Gale Batchelder, and Judson Evans to talk all things poetry (and more), and particularly about their collaborative chapbook, Chalk Song published by Lily Poetry Review Books.

Multiple creative individuals are squeezed in under the spotlight today. I’m happy to introduce you to poets Susan Berger Jones, Gale Batchelder, and Judson Evans to talk all things poetry (and more), and particularly about their collaborative chapbook, Chalk Song published by Lily Poetry Review Books.

Bios:

–Susan Berger-Jones is an architect and poet. Her written and visual work has appeared in Drunken Boat, No Exit, and two anthologies of ekphrastic poems published by Off the Park Press.

–Gale Batchelder lives in Cambridge. Her work has been published Tupelo Quarterly, This Rough Beast, Colorado Review, SpoKe4, and in the poetry anthologies New Smoke (2009) and Triumph of Poverty (2011).

–Judson Evans is a poet whose work has focused on crossing genres and collaboration. He regularly publishes haiku, and the related form of haibun, as well as contemporary lyric poems. He was recently named Haibun Editor of Frogpond, the journal of the Haiku Society of America. In 2007, he was chosen as an “Emerging Poet” by John Yau for the Academy of American Poets and won the Philip Booth Poetry Prize from Salt Hill Review in 2013. His poems have appeared most recently in Folio, Volt, 1913: A Journal of Forms, Cutbank, and Sugar House Review.

What do you enjoy most about writing collaboratively?

–Susan: I enjoy the challenge of listening to others to expand my limited point of view.

–Gale: I love the chorus of voices, the echoes that reverberate, the marrying and birthing of words, images, and feelings. The cave paintings from which we drew our inspiration were also collaborations – over millennia.

–Judson: There’s a give and take and element of surprise. Another writer might introduce new vocabulary, new verbal or rhetorical gestures, new formal devices, and I will feel compelled to swerve toward or away. Also, collaborators in some ways are the ideal readers – they are deep listeners and intuitive responders.

Can you give us a little insight into a few of your poems – which ones were your favorites?

–Susan: I usually edit poems until the original is lost. I don’t want a poem to end. When given a deadline for our book, I stole phrases from Judson and Gale, and from other texts, to finish poems. These now feel like musical scores for blended voices. The poems coalesced, last minute, despite my resistance to closure. “Confetti Score” is an example. It feels interestingly “not me.”

–Susan: I usually edit poems until the original is lost. I don’t want a poem to end. When given a deadline for our book, I stole phrases from Judson and Gale, and from other texts, to finish poems. These now feel like musical scores for blended voices. The poems coalesced, last minute, despite my resistance to closure. “Confetti Score” is an example. It feels interestingly “not me.”

–Gale: One of my favorites is “First Day” which speaks to the “art-makers” – the cave artists, the filmmaker, and my fellow poets. And “One Bloomed” had it’s genesis not in the cave paintings, but from a photo a friend posted on social media, that was of a red (fallen) maple leaf next to a (blooming) blue morning glory.

–Judson: My favorites are those that arose most spontaneously. I spoke/sang “Bow” into existence while walking along the Esplanade in Boston. The momentum of walking, the runners going by, the flow of the Charles River contributed, as did my need to repeat the lines over and over so I could remember and write them down. When I sat down to “record” the poem, I sensed it must have a tense vertical shape on the page, perhaps influenced by the way the poem resonated in my own body.

What role did form play in your collaboration?

–Susan: In Chalk Song I often echoed either Gale or Judson’s form-choices. I would play inside those skins. Normally, I do not know what form I am going to use. Poems find form as I write and re-write them. An exception would be “Residual Sonnet” inspired by John Yau’s “Broken Sonnet.” I liked referring to form in the title, and then saying, well, this form will not hold up. The poem is left over from something else and is already on its way to becoming dust. Nothing is permanent. And forms are not just presence. They too have their ghosts, their inner chambers. It was interesting to find these places, between our poems and within my own. As a response to Gale’s and Judson’s earlier pieces (which both spill down the page/cliff) the sonnet form in “Residual” is hallowed into its inner ear – its own sound mold.

–Gale: The only formal process we used was the intention of responding to each other’s work and the permission – imperative, really – to reshape and reinvent form as the words demanded. I did experiment with different ways to present the poem on the page – blocks of text, caesura in the middle of lines, and in one case, a letter to the filmmaker, Herr Herzog.

–Gale: The only formal process we used was the intention of responding to each other’s work and the permission – imperative, really – to reshape and reinvent form as the words demanded. I did experiment with different ways to present the poem on the page – blocks of text, caesura in the middle of lines, and in one case, a letter to the filmmaker, Herr Herzog.

–Judson: I would describe my overall writing process as one of discovering form as text is generated through intuitive means of sound and image. I see the essence of “form” in the interplay of similarity and difference – repetition and disjunction. In writing with/and against each other, we would often pick up a theme, phrase, sound cluster, and import it into our own poem, where it would become a structural element. An interesting case is the way refrain lines from my poem “Elegy in the Bevel” were borrowed and reshaped in poems by both Gale and Susan. I think there was also a semi-conscious interplay between the “prose poem” (where the poem is in a block /verse paragraph and the basic building block is the sentence) and the lyric poem (where the line is the basic building block and the text is shaped into stanzas or discrete clouds of text.)

What type of project are you working on next?

We are working on a project, that is called for now “Homo –?,” using our own variations on Latin names for Man (and Woman.) We are interested in the ways the “human” has been named by scientists and philosophers. Take the term “homo sapiens sapiens,” for example. An anthropologist in Werner Herzog’s film strongly questions the appropriateness of this designation and substitutes “homo spiritualis.” And – of course – other thinkers have come up with other names to highlight supposedly unique features of our species: Marx’s “homo laborans” or Johan Huizinga’s “homo ludens.” The project addresses questions such as: Is there such a thing as progress? How is being human dependent on language? How does consciousness change as our language changes (both artistic and informational forms of language.) We have developed a way to create prompts for ourselves, share readings, and develop conversations where we are open to sudden shifts, new directions, as we write our way into new territory. There is so much thinking now about where consciousness happens (not just “in the head”) that considers a more open interactivity with world – how have humans adapted and maladapted to generate the creative and destructive forces we are facing. Also, fascinating links between language and music, language and tool making. And, because we are very aware that our poems often echo one another, we are examining reflection, echo, reverberation.

When did you first consider yourself a writer / poet?

–Susan: In my late twenties I took a poetry class at the “Center for Lifelong Learning” at Harvard. There was a homeless man in the class who wrote Dr. Seuss-like poems and spent his class time reading the same worn newspaper. The class showed him such respect. I thought: these are the people I want to spend my life with. I grew up in an art gallery, so being an artist was encouraged, but writing has never been easy for me. In high school my English teachers were frustrated (I could not follow the rules of grammar.) Adrienne Rich spent a whole class using my poem as an example of ‘what not to do to your reader’ (a very helpful lesson.) Through my disability, or inability, I have made beautiful discoveries about following and breaking rules. It took me many years to call myself a poet.

–Gale: I have always wanted to be an “author,” as I called it. I think I became a poet in 2007, although I wrote poetry early in my life, before taking a hiatus of about 30 years. I was hugely influenced in high school by reading Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. The energy, the openness of expression, the rawness. James Joyce is another early influence, as was Greek drama which I read at a very early age – before I had ever heard or knew how to pronounce “Antigone.”

–Judson: I discovered books of romantic poetry that my mother had stored in the attic when I was very young-8-10. The unintelligibility and strangeness of the language and subject matter – Why would anyone write about a “Grecian Urn”? What was a “Grecian Urn” fascinated me. I wrote poems about the beach, dunes, sea gulls, shells in early childhood trips to Montauk Point when I was about 8-9. I was always writing some kind of “poetry” from then on. I liked to “read” things like Blake or Shakespeare – that I did not understand – purely for the sound and sense of a secret language. As a teenager I pored over rock lyrics – Stones, Beatles, Dylan, but also the weirder stuff like Van Dyke Parks, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention. I had access to a wonderful library with a huge contemporary poetry collection –The Osterhaus Free Library in Wilkes-Barre, PA – and I read my way through Gertrude Stein, H.D., many of the modernists; then Creeley, Duncan, Levertov. On to Jerome Rothenberg’s anthologies and postmodern and experimental poetry. In college I became obsessed with Japanese culture and haiku and started to experiment.

–Judson: I discovered books of romantic poetry that my mother had stored in the attic when I was very young-8-10. The unintelligibility and strangeness of the language and subject matter – Why would anyone write about a “Grecian Urn”? What was a “Grecian Urn” fascinated me. I wrote poems about the beach, dunes, sea gulls, shells in early childhood trips to Montauk Point when I was about 8-9. I was always writing some kind of “poetry” from then on. I liked to “read” things like Blake or Shakespeare – that I did not understand – purely for the sound and sense of a secret language. As a teenager I pored over rock lyrics – Stones, Beatles, Dylan, but also the weirder stuff like Van Dyke Parks, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention. I had access to a wonderful library with a huge contemporary poetry collection –The Osterhaus Free Library in Wilkes-Barre, PA – and I read my way through Gertrude Stein, H.D., many of the modernists; then Creeley, Duncan, Levertov. On to Jerome Rothenberg’s anthologies and postmodern and experimental poetry. In college I became obsessed with Japanese culture and haiku and started to experiment.

When did you decide to work on a collaboration?

–Gale: The three of us met in a poetry workshop that continued for many years. I had so much admiration for Susan and Judson’s work and learned so much from them that I wanted to have a different kind of – a poetic – conversation with them. But we didn’t simply want to write poems together – that didn’t work for us. We wanted a kind of “call and response” (like American Gospel music) collaboration. I sing in a chorus, and I have always been interested in the way that poems written by individual writers can be like different voice parts or instruments – echoing, clashing, harmonizing.

–Susan: So grateful that Gale had this idea. Love her chorus analogy.

–Judson: I have taught at a Music Conservatory – Boston Conservatory of Music & now (since the merger) Berklee College of Music for most of my life, and, of course, in the world of performance, whether music, dance, opera, or theater, everything is collaborative. I’ve had so many opportunities to collaborate in this performative space with composers like Mohammed Fairouz and Marti Epstein and with dancers, such as Boston’s TeXtmoVes, directed by Karen Klein. As lover and practitioner of Japanese forms of poetry – especially “renku”, or linked verse. I’ve written with other haiku poets for many years. In another context, I worked on a collaborative project with videographer Ray Klimek exploring the Italian renaissance poet Petrarch’s climb of Mont Ventoux in Southern France – the first example of anyone in the western world climbing mountain for the sake of “taking in the prospect”. In other words, the beginning of the concept of “landscape.” That project resulted in a different sort of outcome. Ray produced a film “Remote Viewing” and a book of photographs, while I wrote a book of poems – “GEAR.” These works influenced and interacted with each other but were in the end separate entities. Working with Gale and Susan was a much more sustained and engaged interaction because we constantly read and re-read each other. We developed an intimate sense of each other’s preoccupations, verbal gestures, personal vocabularies and influenced each other’s editing and revision.

How did this change how you see yourself as a poet?

–Susan: I do not see myself as a poet without Gale and Judson’s music playing in the back of my head. I collaborate with all of the poets I read, reworking their poems, changing the sounds. We were all babies at one point. We learned to communicate through re-sounding, re-seeing, re-touching. In this sense all experience is inherently a collaboration, until we die.

–Gale: It has helped me to understand how much a reader or a collaborator inhabits my work and makes it their own – the many meanings they see, what they hear, how their experience shapes my meaning. “Meaning” isn’t something I create or give to the poem – it arises out of that participation. So often Susan and Judson would comment on my poems and I would be both mystified and enthralled by what they brought to the poems and what they took from them.

–Judson: I think collaboration makes the role of poet seem a lot less mystified and private. Poetry becomes creative work where you bring whatever verbal, imaginative, or formal resources you can muster into the fray. So much of collaboration is listening and thinking-feeling into another artist’s work and creating a response that doesn’t stop with the gesture you’ve made. That ongoing-ness tends to make me think of my writing as about response and relationships, as much as personal vision or autobiographical themes. I think we have all been influenced by John Yau’s sense of the poet as creator and catalyst, ready to absorb whatever is inspiring and new in other artists’ work, and also as a ready participant improvising with others.

How do you research markets for your work, perhaps as some advice for not-yet-published poets?

Susan, Gale, & Judson: Really the best way is to look at where poets you admire are published, and then submit there. You can also create your own community: support each other by publishing yourself in hand-made books.

What would you say is your interesting writing quirk?

–Susan: I think about eating snacks while writing (writing makes me hungry.)

–Gale: I’m not quirky.

–Judson: Throwing together chance phrases from wildly different sources; switching from medium to medium; reciting lines into my i-phone; writing them out on a legal pad; transcribing into a computer file; superimposing the lines over a photograph using the “Snapseed” app; cannibalizing old poems from old journals and using erasure; or recombination to get something new.

As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up?

–Susan: A belly dancer (as I wrote to my parents. I meant: “ballet” dancer.)

–Gale: An “author”

–Judson: A “writer”

Anything additional you want to share with the readers?

The one thing that we have in common is that we are curious about everything and are non-judgmental about what poetry ‘is’ or ‘is not’. We have heard too many people attempt to define what works or what does not work in an artwork, and, yes, these are seasoned professionals with experience beyond (my and our) imaginations. Yet the beauty of being a poet is to honor one’s strengths and weaknesses, to re-frame these into conversations. Do not try to correct your weaknesses. They are hidden talents. We were very lucky to meet a poet such as John Yau. It is important to find teachers who support you in this open way, and who believe that poetry is a means to open up conversations.

For me (this is Judson speaking) I think being a college Instructor of poetry has made me hyperconscious of not wanting to shut down any directions my students want to move in. I’ve so often found myself ‘deprogramming’ students stifled and stymied by the sense that poems are coded information that needs dissection. Personally, I read try to read as wide a stylistic variety of poetry as I can, and this is true of Susan and Gale, as well. We share our excitements and enthusiasms and have had occasion to work through books we admire (thinking here of Diane Suess’s “frank: sonnets.”) I especially try to bring a lot of wide-ranging contemporary poetry into the classroom and invite young pots to read and talk about their work. I find that collaborative poetry writing often helps them become more open.

Links:

Amazon buy page | Susan’s website | Gale’s profile on Tupelo | Publisher website | Noon – Journal of the Short Poem

Thank you all for being here today!