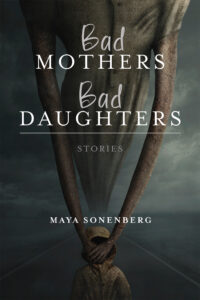

Short story writer Maya Sonenberg joins me today to chat about her new collection, Bad Mothers, Bad Daughters.

Short story writer Maya Sonenberg joins me today to chat about her new collection, Bad Mothers, Bad Daughters.

Bio:

Maya Sonenberg’s story collection Bad Mothers, Bad Daughters is the recipient of the 2021 Sullivan Prize in short fiction and will appear in August 2022. Previous books and chapbooks include Cartographies (winner of the Drue Heinz Prize), Voices from the Blue Hotel, 26 Abductions, and After the Death of Shostakovich Père. Her stories and essays have appeared in Conjunctions, Fairy Tale Review, Electric Literature, The Collagist, DIAGRAM, and many other literary journals. The daughter of two painters, she was raised in New York City, and studied with Annie Dillard at Wesleyan University and with Robert Coover, John Hawkes, and Meredith Steinbach at Brown University, where she received her MFA. She is a professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Washington, and lives in Seattle with her family.

What do you enjoy most about writing short stories?

I love the way writing short stories allows me to plug in to the intuitive and inventive, even as I organize each story carefully, often according to some external structure. I guess I love the interplay between freedom and constraint as I write short stories.

Can you give us a little insight into a few of your short stories – perhaps some of your favorites?

Rereading my forthcoming collection, Bad Mothers, Bad Daughters, during the copyediting and proofreading process has allowed me to rediscover some favorites! I still get a kick out of the passage in “Princess of Desire,” where the narrator creates anagrams out of the word “boredom” while she’s in bed with various men she doesn’t actually feel attracted to. I feel deeply empathetic toward the young girl wandering around Paris as she avoids an abusive uncle and considers her heritage in “The Cathedral is a Mouth.” In that story, I allowed myself to invent completely illogical fantastical elements (at one point, the protagonist shrinks, is swept under the shawl of an old woman, and transported 100 years into the past) which I found could convey the protagonist’s emotional state better than any realistic scene I might have written. I am often interested in creating movement through a short story using something other than plot, and find this comes through clearly in “Hunters and Gatherers.” While there is narrative in that story—the real time events take place over a single summer afternoon—the actual movement or change in the story takes place on the intellectual plane: at first the story posits that men and women, boys and girls, interact with each other and the world in quite different ways, but by the end, I hope the story successfully conveys that neither are purely hunters or gatherers. Perhaps this is the most hopeful story in my collection!

What genre are you inspired to write in the most? Why?

I find myself returning most often to fairy tales, contemporary retellings of old tales, and contemporary stories that have, as Kate Bernheimer calls it, a “fairy tale feel.” My whole writing life I’ve been trying to write fiction that avoids the domestic drama plot and questions the mechanisms of psychological realism. Fairy tales, with their flatness, abstraction, and unexplained magic provide me with one avenue for doing that. They call attention to the fact that we’re in the presence of story, of art, but they provide engrossing, engaging reads at the same time.

What exciting story are you working on next?

I’m currently working on several nonfiction projects, and one mixed project: a miniature book about miniatures that will include brief discussions of what miniatures are to me and why we’re so drawn to them, as well as a fairy tale broken into tiny chapters about an old woman and a black fox.

When did you first consider yourself a writer?

When did you first consider yourself a writer?

When I was in second or third grade, we were asked what we wanted to be when we grew up. I responded: a writer or a fashion designer. The world is lucky I didn’t choose fashion designer! That’s the first time I can remember making an actual choice to be a writer, but I remember telling the most basic story when I was drawing as a tiny child, saying “Now it’s blue’s turn, now it’s yellow’s.” When I was in high school, I began to think of writing as the art I wanted to pursue and to truly imagine myself becoming a Writer, with a capital W.

How do you research markets for your work, perhaps as some advice for writers?

I often talk about this process at length with students but will try to boil it down here. I have an active list of about 50 literary journals I would be happy to see my work appear in and which I think might love my work in return. As I read short stories, I think about whether they share qualities with my own work. If the answer is yes, I figure out where they were first published. If I’m finding them in a literary journal, it’s easy! If they’re in a collection or anthology, the book usually lists the journals in which they appeared. I then track down other publications by the same authors and add those journals to the list. I visit the websites of the journals on my list and see if they link to other journals; those are usually ones with which they share an aesthetic. I read other stories published in the journals on my list, and if they also share qualities with my own work, I figure out where else those authors have been published.

What would you say is your interesting writing quirk?

I’m not sure it’s a quirk, but I write best and most productively when I remove myself from my family. Starting about a dozen years ago, I’ve taken myself on writing retreats once or twice a year.

Anything additional you want to share with the readers?

No one else will ever care about your writing as deeply as you do yourself. It’s important to develop internal motivations to keep writing over the long haul: what makes it more interesting than anything else you could be doing right then? What makes it more fun?

Thanks for being here today!